38 Incredible Facts on the Modern U.S. Dollar

The Money Project is an ongoing collaboration between Visual Capitalist and Texas Precious Metals that seeks to use intuitive visualizations to explore the origins, nature, and use of money.

We’ve previously showed you 31 Fascinating Facts About the Dollar’s Early History, which highlighted the history of U.S. currency before the 20th century. This was a very interesting period in which we looked at the money used by the first colonists, the extreme bust of the Continental currency, the era of privately-issued bank notes, and Congress’ emergency issuance of the fiat “greenback” during the Civil War.

However, the modern era of the U.S. dollar is just as interesting. We have it starting in 1913, when the Federal Reserve Act was passed by Woodrow Wilson. Not only did it establish a new central bank, but it also gave the Fed the authority to issue the Federal Reserve Note, which is now the dominant form of U.S. currency both domestically and abroad.

A New Legal Tender

Leading up to the 20th century, there were four main forms of U.S. currency being used:

- Gold and silver coins

- Gold and silver certificates

- Commercial bank notes, issued by private banks and backed by government bonds

- “Greenbacks”, a fiat currency declared legal by Congress to help fund the Civil War

In 1913, however, the Federal Reserve Note was authorized as U.S. currency. The new notes were supposed to be backed by gold or other “lawful money”, based on the stipulations of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913.

However, this only lasted about 20 years. By the time of the Great Depression, the Fed considered itself to be in a tight spot. It simply did not have enough gold to back all Federal Reserve Notes and Gold Certificates in circulation, and at the same time wanted flexibility with monetary policy to fight deflation and unemployment.

In 1933, the Emergency Banking Act was passed by President Roosevelt, and Executive Order 6102 was also signed. The latter move famously criminalized monetary gold, and ended the gold standard.

After all, if gold can’t be legally owned, it can’t be legally redeemed.

Modern Paper Money

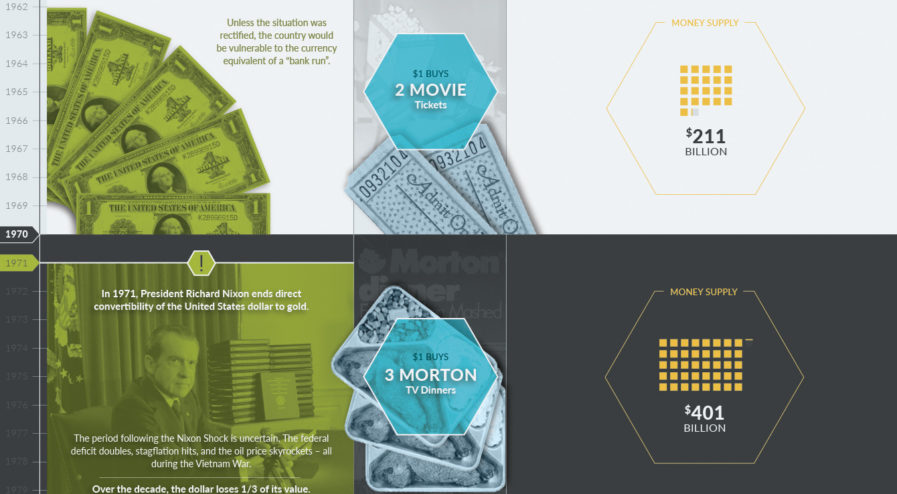

After a brief return to a pseudo gold standard after WWII, Nixon severed all remaining ties between gold and money in 1971. Since then, U.S. money has been purely fiat, and backed by the government rather than any physical commodity or precious metal.

Some facts on today’s paper money:

- There is $1.54 trillion of U.S. currency in circulation, and 97% of that is Federal Reserve Notes

- Over two-thirds of all $100 bills are held outside the U.S.

- Dollar bills can be folded at least 8,000 times, which is 20x more than a normal sheet of paper

- That’s because dollar bills are made of a special 75% cotton and 25% linen blend, patented by Crane & Co.

- The U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing produces 38 million notes every day, worth $541 million

- The two facilities, located in Washington, D.C. and Fort Worth, Texas use 9.7 tons of ink per day

- For 2017, the Fed ordered 7.1 billion new notes, worth $209 billion

- More than 70% of these notes are used to replace damaged ones

- Notes with smaller denominations ($1, $5, $10) tend to last for shorter periods of time, due to more frequent usage

Coins

The coins used today are similar to U.S. Federal Reserve Notes in that their face values tend to greatly exceed their intrinsic values.

This is because cheaper metals such as copper, zinc, and nickel are used instead of gold or silver.

- The average lifespan of a coin is 25 years, according to the U.S. Mint

- It’s estimated that Americans throw away around $62 million of coins every year

- In 2016, the U.S. Mint produced 16 trillion coins, valued at over $1.09 billion

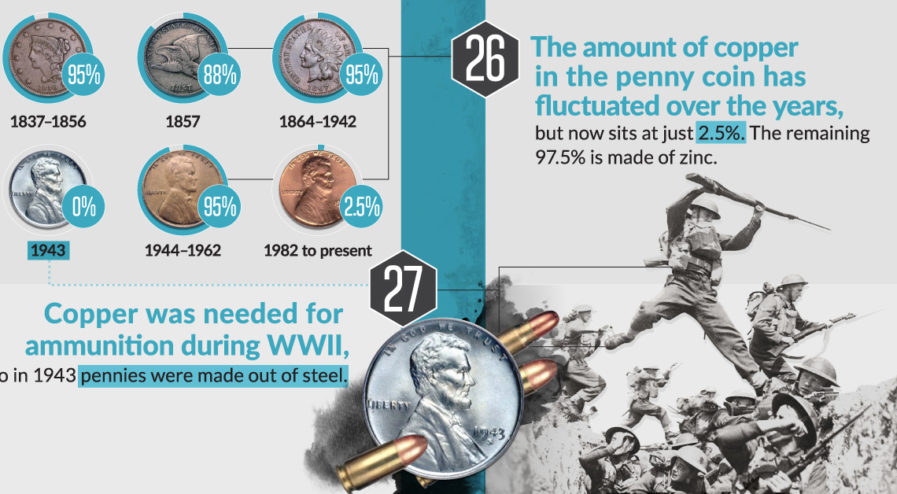

- The amount of copper in a penny has fluctuated over the years. It ranges from 0% (in WWII, pennies were made of steel so copper could be used for ammunition) to 95%.

- Today’s pennies are 2.5% copper, with the remainder being 97.5% zinc

Embed This Image On Your Site (copy code below):