From the 10 years of military dictatorship between 1948-1958 to the impeachment of Carlos Andrés Pérez for corruption in 1993, Venezuelan politics have often been both rocky and eventful.

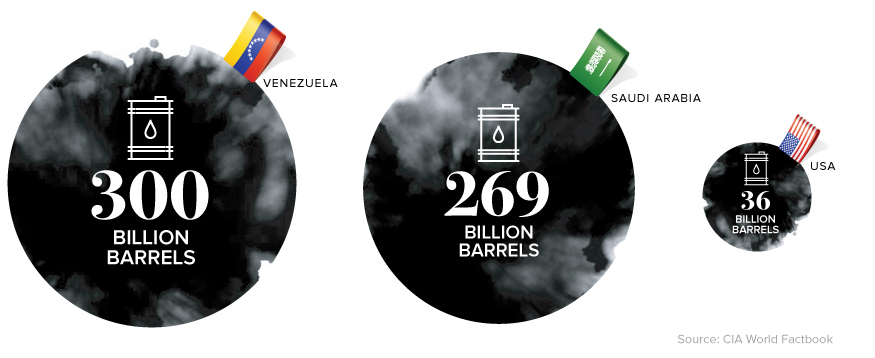

But despite these challenges throughout its history, no one has ever denied Venezuela’s economic potential. After the discovery of oil in the early 20th century, the nation quickly built its economy on back of black gold – and even today, Venezuela leads the world in proven oil reserves with 300 billion barrels.

Early on, Venezuela’s oil was a game-changer.

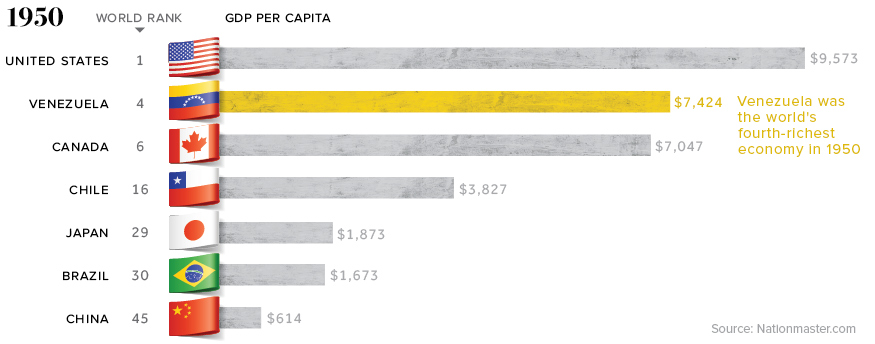

By 1950, as the rest of the world was struggling to recover from World War II, Venezuela had the fourth-richest GDP per capita on Earth. The country was 2x richer than Chile, 4x richer than Japan, and 12x richer than China!

Unfortunately for Venezuela, this wealth wouldn’t last – and an over-reliance on oil would soon decimate the economy in unexpected ways.

The Downfall of Venezuela’s Economy

From 1950 to the early 1980s, the Venezuelan economy experienced steady growth.

By 1982, Venezuela was still the richest major economy in Latin America. The country used its vast oil wealth to pay for social programs, including health care, education, transport, and food subsidies. Workers in Venezuela were among the highest paid in the region.

However, as you’ll see in the following animation, from there things went quickly downhill. In the mid-1980s, an oil glut and a free-falling oil price ended up decimating the Venezuelan economy, which was unable to diversify away from energy.

Today, Venezuela has one of the poorest major economies in Latin America – and as the current crisis rides itself out, the IMF foresees it getting far worse. By 2022, the organization predicts Venezuela’s GDP per capita (PPP) will be just $12,210, which would be a massive economic setback – the Venezuelan economy would be even poorer than it was many years before the Chávez era started.

Flying Too Close to the Sun

Although oil revenues are tempting to rely on to maintain social order, they come with a degree of unpredictability. According to OPEC, Venezuela still relies on oil for 95% of its exports, which means that any fluctuations in oil price can be the difference between immense wealth and near-poverty.

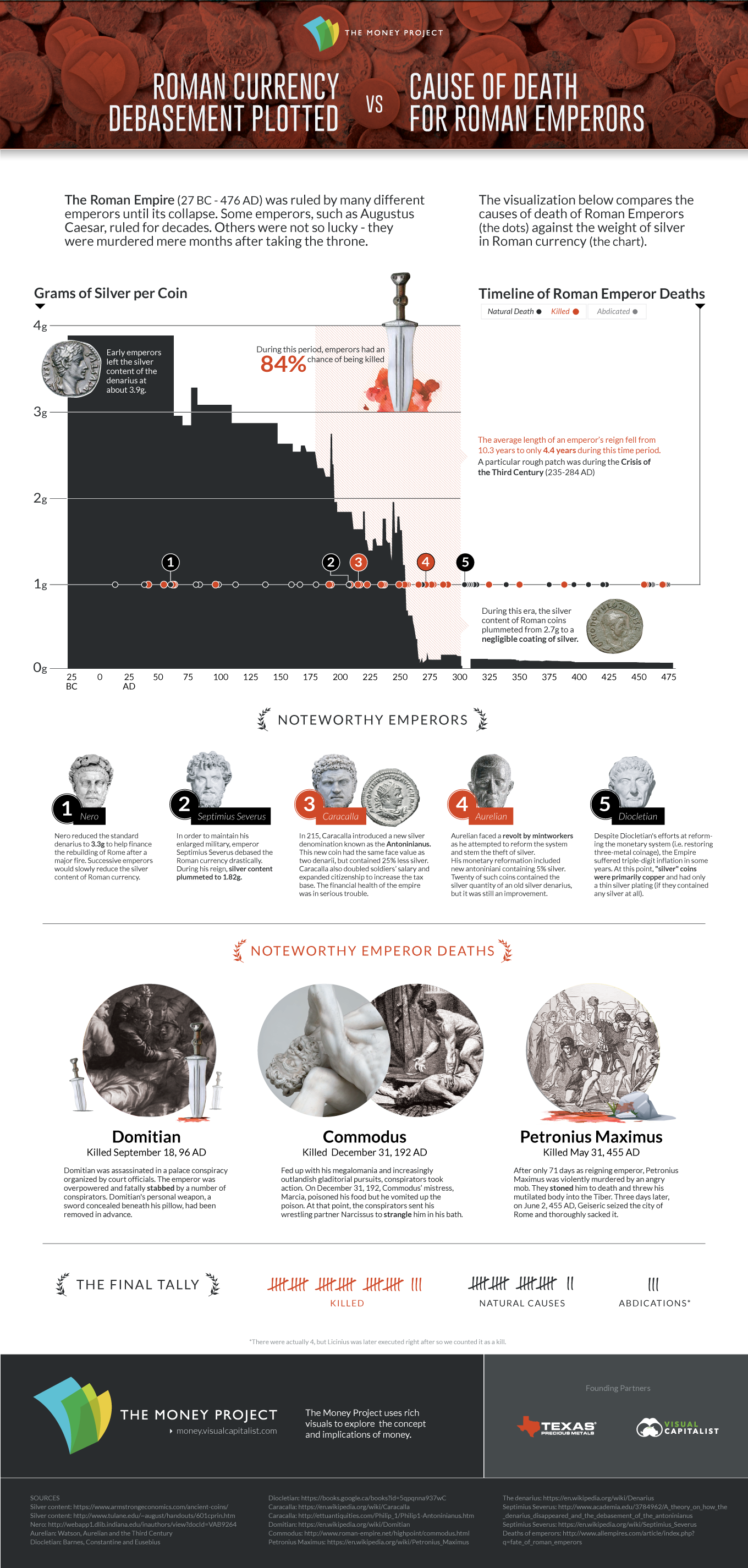

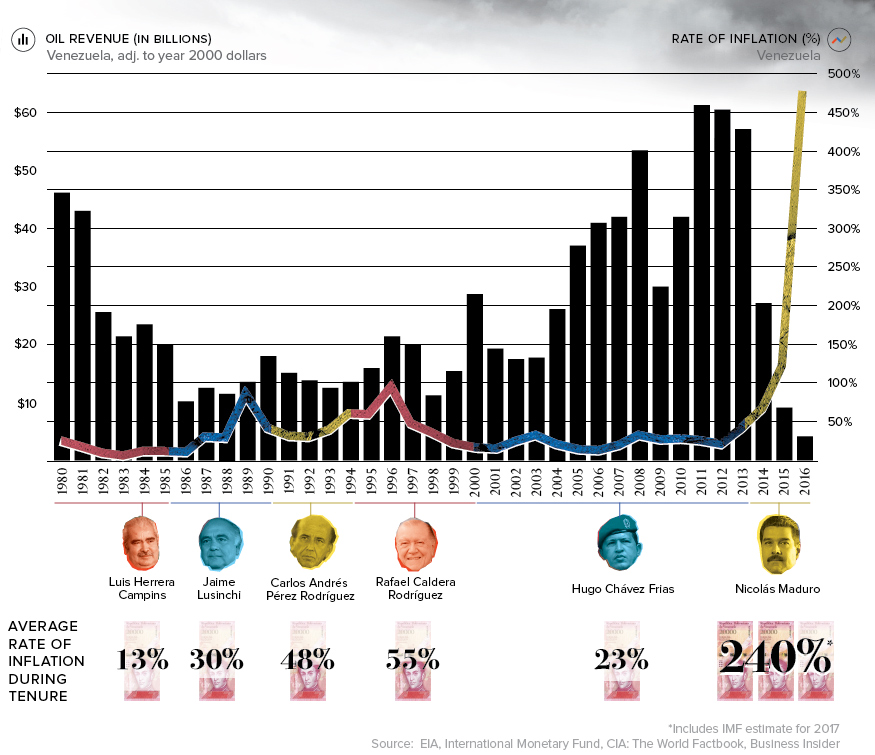

The above graphic shows Venezuela’s oil revenues (in 2000 dollars) against the rate of inflation – and it symbolizes the story of Venezuela’s recent economic history as succinctly as possible.

After the oil glut in the 1980s, Venezuela’s oil revenues dropped significantly. It was then that Venezuela had its first bout with inflation, where rates peaked in 1989 (84.5% inflation) and later in 1996 (99.9% inflation). Without sufficient money coming in, the country had to rely on its printing presses in an attempt to maintain living standards.

In 1998, Hugo Chávez was elected with the promise that Venezuela could reduce poverty and step up living standards by leaning even more heavily on its energy wealth. The recovery of oil prices helped this come true in the 2000s, and Chávez later passed away in office in 2013.

A Temporary Fix

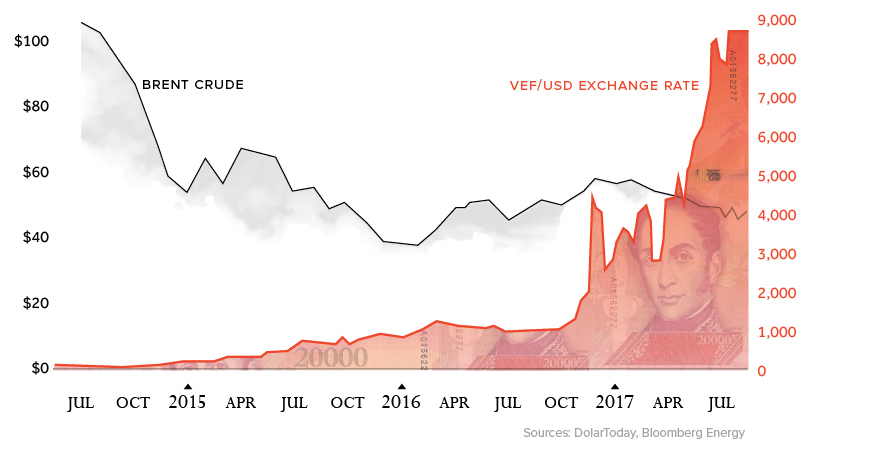

Nicolás Maduro, who took over after the death of his predecessor, saw oil prices crash almost immediately, and it was clear that Venezuela’s intense battle with inflation was only just beginning. The national currency, the Venezuelan bolívar, would soon be almost worthless.

The details of today’s crisis and intense hyperinflation are widely shared.

The country has massive shortages of food, electricity, and other essential goods, and violence is escalating in Caracas. More recently, the government is attempting to tighten its grip around power, and mismanagement of the economy has led to people starving on the streets. People are calling the situation a humanitarian crisis, which is extremely disheartening to see in what was once one of the richest countries on the planet.

And while the current condition of Venezuela is a tragedy in itself, the country’s inability to live up to its true economic potential is nearly just as devastating.

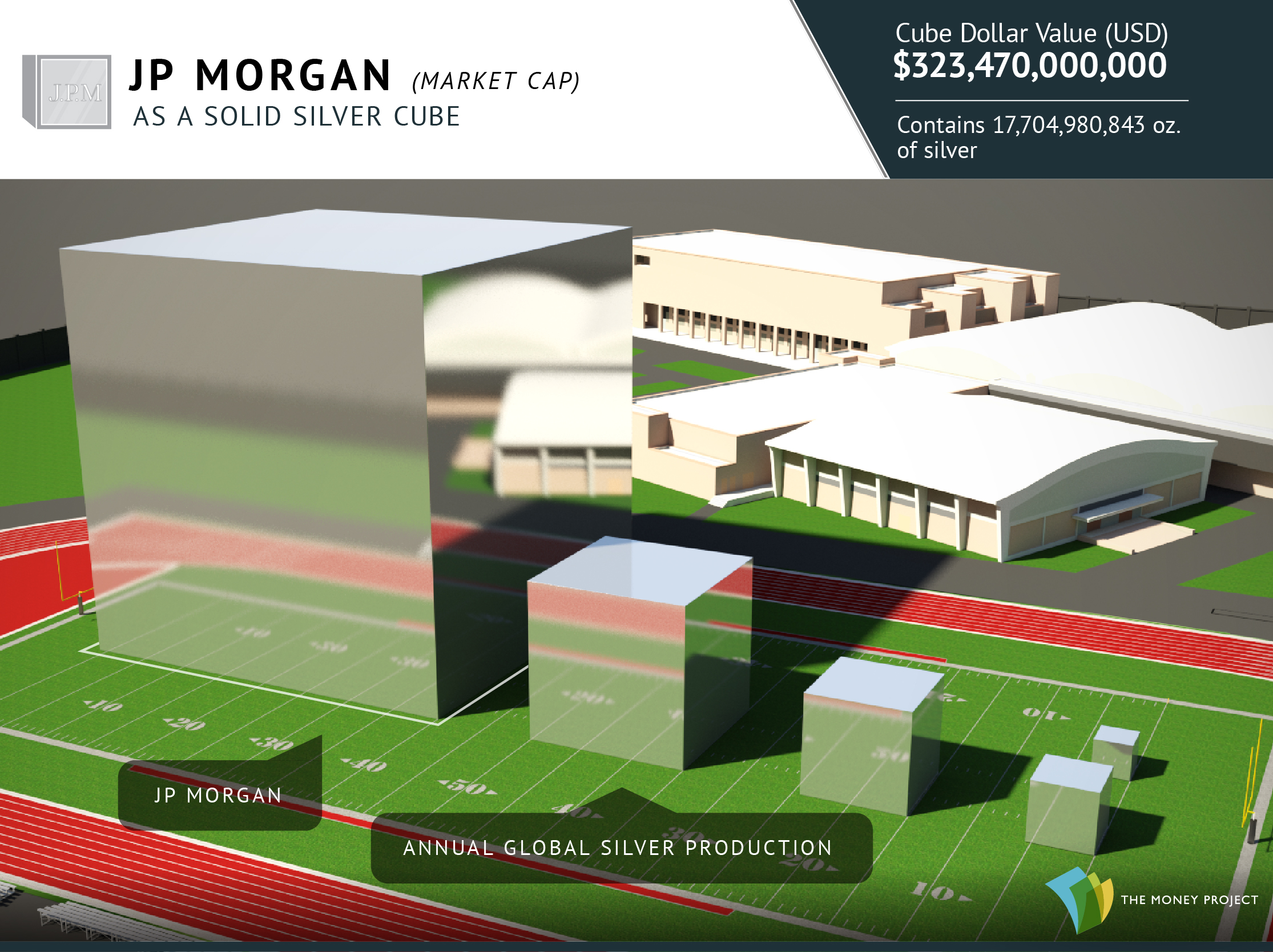

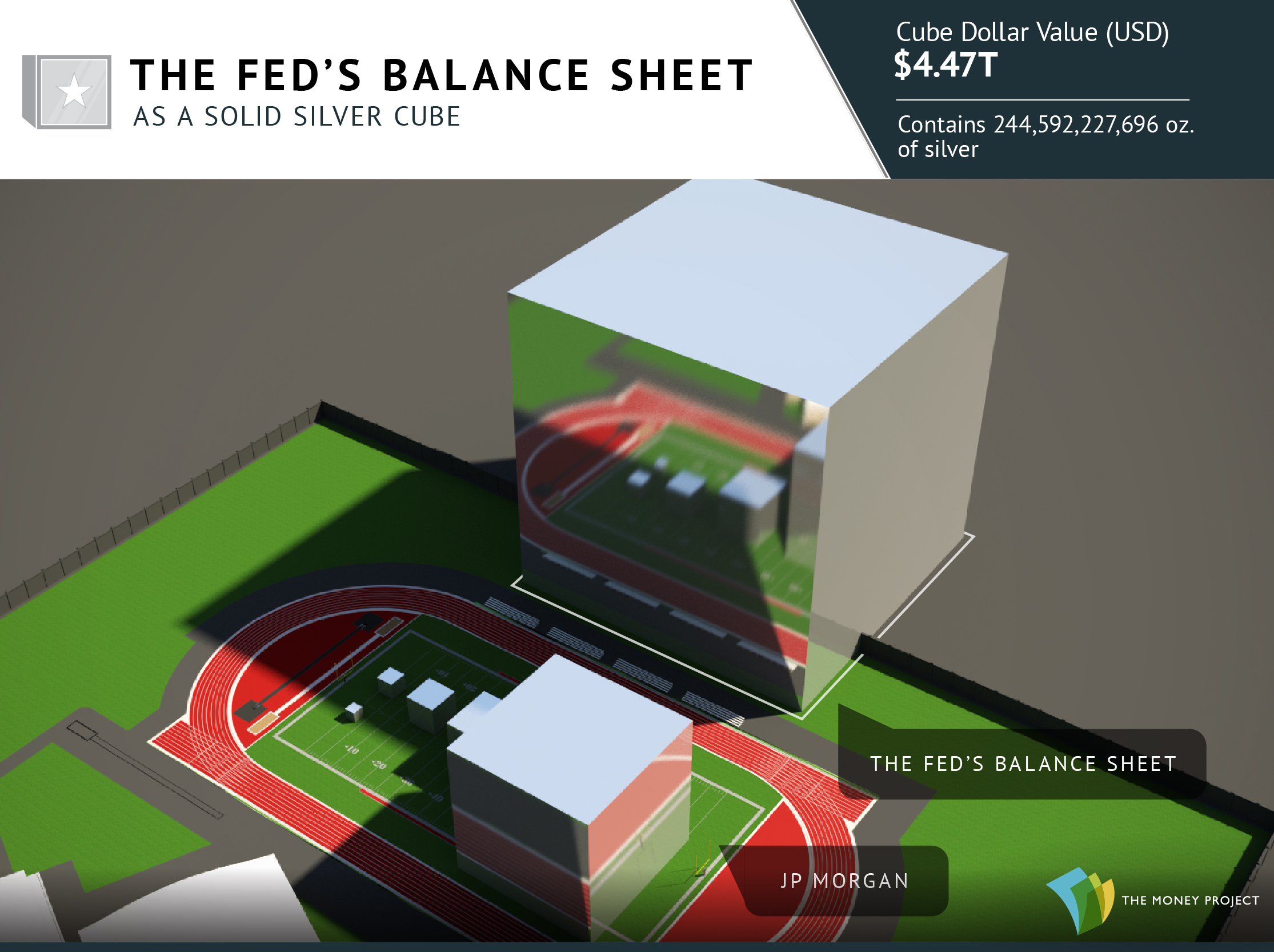

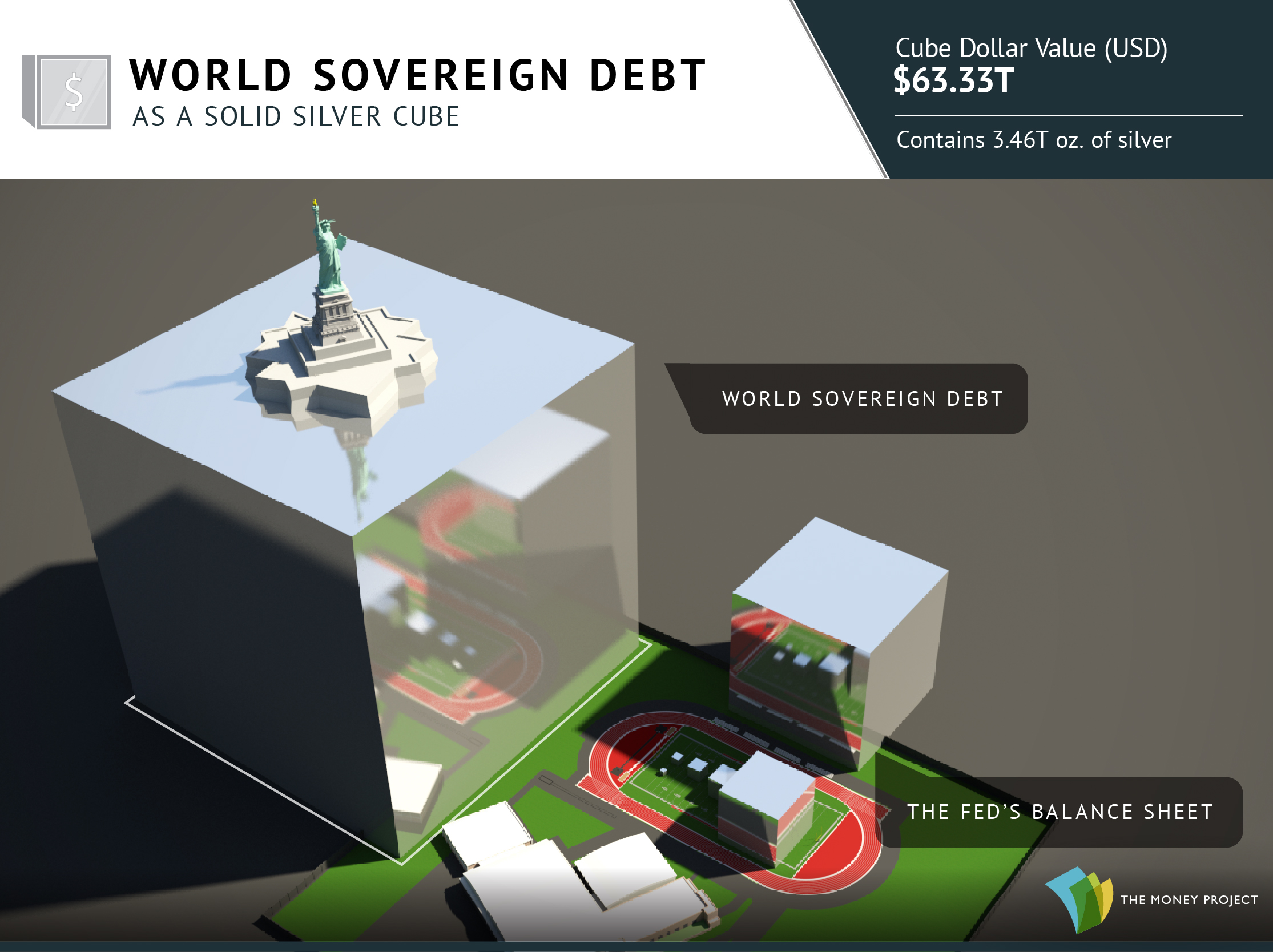

The Money Project

The Money Project is an ongoing collaboration between Visual Capitalist and Texas Precious Metals that seeks to use intuitive visualizations to explore the origins, nature, and use of money.